Geostaza Komiža -

THE OLDEST ROCKS IN THE ADRIATIC WERE FORMED FROM SALT AND LAVA

1. INTRODUCTORY PANEL

Dear visitors- geoexplorers,

You are in a volcanic triangle at the edge of the Adriatic Sea, a triangle whose three points are the Komiža Bay, the islet of Jabuka and the island of Palagruža. This is the only area in the Adriatic where you can come across volcanic rocks. The trail spreading out before you will tell you an epic story on geology and explain the life of Komiža, its history and customs.

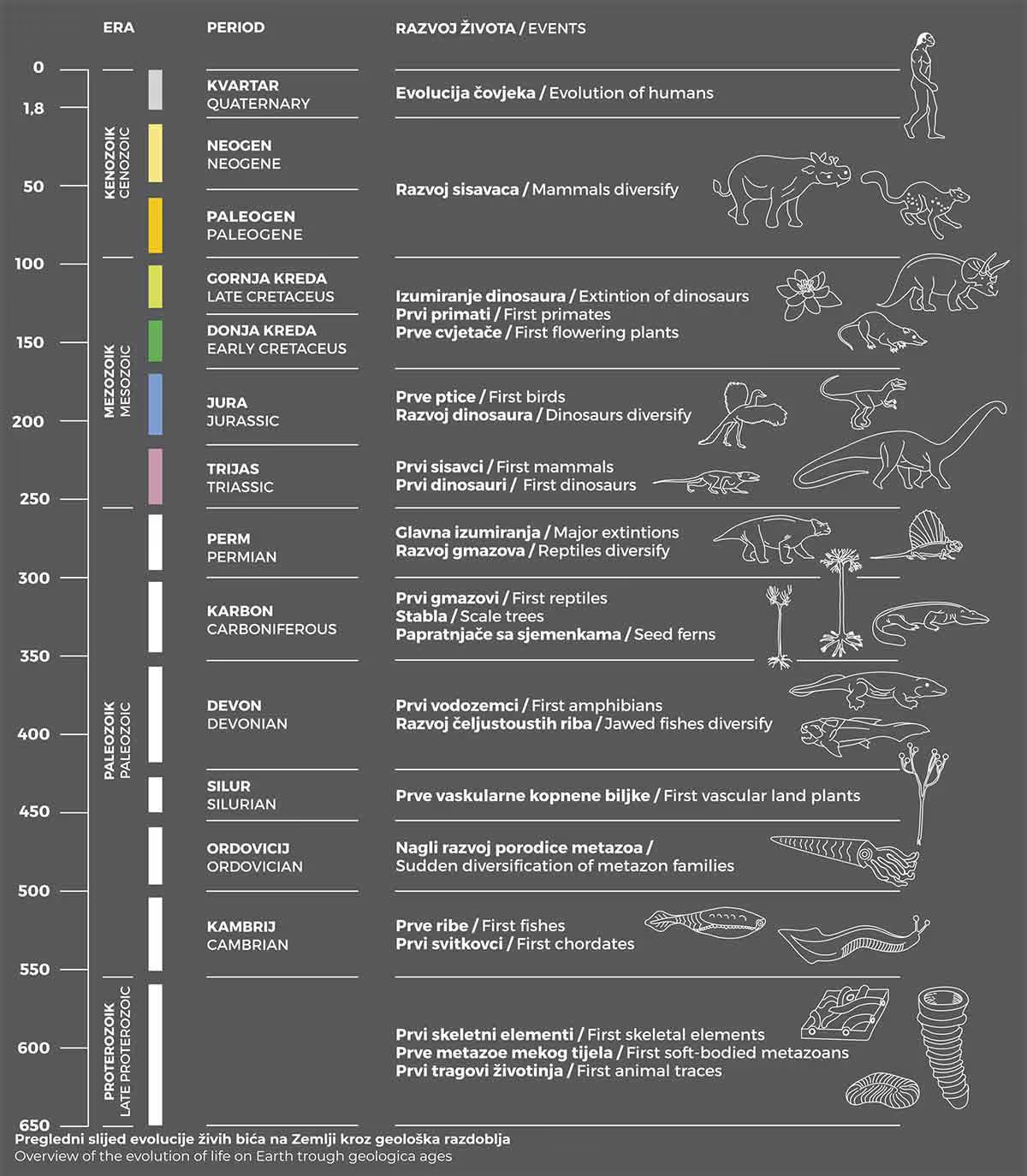

Our epic journey starts 220 million years ago, in the Early Triassic Periodwhile dinosaurs ruled the Earth. During that time, there was an active volcano in the area of Komiža Bay. Petrified lava, volcanic bombs, ash, salt and sedimentary rocks are all remains of this volcano whose parts are still visible today.

During the Cretaceous Period, Komiža’s volcano was covered by shallow sea which had deposited its sediments for millions of years. Most of the island of Vis is built from these shallow water sediments/limestones. Namely, millions of years of this geological period have steadily covered the volcano with layers of sedimentary rocks. These rocks, some of which were a few kilometers thick, have built the Adriatic Carbonate Platform which had split from the African continental plateand floated to the present-day Adriatic.

Over the course of the past couple of million years, tectonic quakes at a depth of more than 5 kilometers have formed a large salt diapir which, due to itssmaller density, started to float up towards the surface, dragging with it blocks of adjacent volcanic rocks. In the Quarternary period the salt diapir in the shape of a large underground mushroom finally broke through to the surface. At the same time, the rains and the sea continuously washed out the diapir structure, resulting in the formation of the present-day Komiža Bay.

2. CASTLE KOMUNA

In the past centuries the island of Vis was under constant threat from pirate attacks, more than any other Dalmatian island, and particularly the town of Komiža, which not only faced the open sea but also had a budding fishing industry as early as the 16th century and was known to export large quantities of salted fish to Venice. Salted fish was highly valuable goods, and the reason why pirates often went after Komiža's fishing boats carrying a heavy load of barrels stuffed with highly wanted produce. Pirates often captured the fishermen and later sold them as galley slaves.

The Venetian state official on the islands of Hvar and Vis, governor Ioanis Grimani, succeeded in convincing Venice to erect a fortress in Komiža's port, of which there is record on the stone lintel above the main fortress gates, right next to the Venetian coat of arms. The words carved into this lintel say that governor Ioanis Grimani is to be merited for the construction of this fortress in 1585. OPVS CVRA IOANIS GRIMANI COMITIS ET PROVISSORIS SVB ANNO DOMINI MDLXXXV

However, this fort would have remained uncompleted because of the shortage of state funds, had it not been for the local fishermen who paid taxes on the sardine catch from the rich fishing grounds in the Trešjavac Bay on the southern coast of the island of Biševo. Words carved into stone at the top of the nothern fortress wall speak of the construction being made possible by income procured from the rich fishing post of Trešjavac (Tresliavac): DEO. GRATIA ICH EST OPERA DI POSTA TRESLIAVAC 1.5.9.2.

This tells us not only about collective solidarity of fishermen endangered by continous pirate attacks, but also about the incredibly advanced fishing industry in the 16th century Komiža, unmatched on the Adriatic coast. The „Komuna“ fortress in Komiža is unique in Croatia in that it was built by the joint effort of Komiža fishermen whose bountiful catch secured enough income tax to complete the construction of this fortress erected for pirate defense.

3. NEPTUNE – KOMIŽA'S STORY ABOUT THE BEGINNINGS OF THE FISHING INDUSTRY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

For hundreds of years Komiža's fishermen caught small pelagic fish (European pilchard, anchovies, mackerel) and salted them in large wooden barrels. According to written record from 1873, the Vis fishermen used over 340 tonnes of salt yearly to conserve the fishand around 20 thousand barrels or one million kilograms of salted fish was exported to Greece or Italy.

Salted pilchards were a staple food aboard sailing ships for centuries. The decrease in sailing as the dominant mode of maritime transportation, resulted in the decreased demand for this most important export produce of Dalmatia. Just around this time of the waning interest in Dalmatian fishermen’s staple produce, the first cannery in the Adriatic was founded. The first cannery by the name of Fratelli Mardesichwas founded by two brothers Mardešić in Komiža in 1870. This was only 10 years after the discovery of bacteria by the French scientist Louis Pasteur in 1860, which enabled pasteurization and consequently conservation of food in cans. The Fratelli Mardesich cannery in Komiža was founded 39 years before the beginning of industrial fish processing in the United States, which began in 1909.

It was the beginning of a new age in the history of fishing in Komiža. After the foundation of the first cannery on the Adriatic in 1870, this fishing town became, in a short while, the centre of fishing industry in Dalmatia.In 1911 there were as many as 15 canneries in Dalmatia, six of which were owned by foreigners from Trieste and Vienna, and as many as nine owned by Komiža locals. Komiža’s fishermen also spread their businesses beyond the Adriatic Sea – they started fish processing plants on the Atlantic coast, near Cape Finisterre in Spain’s Galicia. This enterprise in organized industrial fishing and fish processing from the 1890s until the beginning of WWI, represents the beginning of Spain’s fishing industry.

4. KAMENICE – A STORY ABOUT WATER AND ARRIVAL OF POPE ALEXANDER III

The geological substratum of Komiža Bay is formed in such a way that it retains water underground. There are a number of wells with potable water in the town of Komiža. This water surfaces on the very edge of the coast, on Komiža’s beaches. These potable water springs attracted and sustained life in the area, consequently making this spacious bay on the southwestern coast of Vis one of the key maritime points on the trans-Adriatic route known as the Diomedes’ Route, well known and traversed by Greek and Roman seafarers.

Komiža’s beaches with potable water springs in the Komiža Bay were important to old seafarers who needed to stock up on fresh water. Commanders of Pope Alexander the Third’s fleet also knew this, when they arrived on Pope’s galleys in the Komiža Bay on March 10th 1177, on their way from Vieste to Venice. Fresh water springs are the most probable reason why Pope’s galleys decided to stop over on the beaches of Komiža, in addition to the fact that a path led from the Kamenice beach straight to the Benedictine monastery on the hill, where Pope and his entourage set out for in order to visit the Benedictine monks and consecrate their Church of St. Nicholas. The path leading from this beach winds through an interesting geological landscape of andesitic lava and black stone balls (volcanic bombs) which draw us to the conclusion that a surface volcanic eruption once took place here.

5. PETRIFIED LAVA AND COLORFUL "FLOWERS" OF MINERALS

More than 200 million years ago, this area’s main feature was a raging, fuming volcano. Melted rocks from the Earth's mantle protruded the surface through the deep fractures of the crust.Hot and glowing lava cooled rapidly, creating volcanic hills in the process. This is how mineral-rich volcanic rocks were formed. Subject to pressure from gases and vapors, the most beautiful of minerals, prehnite,crystallized into mineral ‘flowers’ which can be seen here at the Kamenice beach. In addition, this petrified lava also contains a very small amount of gold, which posseses no economic value in this context of natural environment.

6. VOLCANIC BOMBS ON THE RIMS OF AN ANCIENT VOLCANO

Some 220 million years ago the Komiža Bay landscape was dominated by a large volcano. Its massive eruptions sent lava soaring into the air. While rotating in the air, lava turned into round balloon-like shapes which, as they fell back onto volcanic ash, would further transform into volcanic agglomerates, a mixture of volcanic bombs and volcanic dust. The Kamenice beach is the very place where different types of rocks came into contact: volcanic tuffs, andesite lavas and limestones. It is due to this geological fact that Komiža and the whole island of Vis have their own underground water. Namely, watertight andesite lava retains water that penetrates trough water-permeable limestone and tuffs, saturating the cracks in rocks and finally winding its way to the surface of this beach. Fresh water springs like these secured Komiža’s population from the dangers of drought and excessive dependency on rainwater reservoirs. Compared to other Dalmatian towns, Komiža had on average a much smaller number of rainwater reservoirs, because freshwater in Komiža was available in wells and springs.

7. VOLCANIC AGRICULTURAL FIELD

Eroded deposits of mud and ash from the deeply buried volcano basin

Volcanic marine basin was a shallow environment, ideal for sedimentation of salt, volcanic outflowsand and different types of marine muds: carbonate mud became dolomite and limestone, clay mud became marl and silt with a higher content of volcanic ash formed pyroclastic rocks (tuff and tufa).

Over the course of time, these rocks became deeply buried in the Earth's crust, only to be lifted back to the surface again later, pushed by the force ofthe salt diapir.Throughout this process of surfacing these rocks were fractured and folded, resulting in strong surface erosion. The surface erosion of these softer rocks formed a large bay in the area of present-day Komiža, with a fertile agricultural field rich in volcanic minerals. After the last Ice Age, the sea flooded the Cove, forming the present-day Komiža Bay.

8. DRAGOVODA WELL

Komiža's water supply line was built in 1964. Before water was brought directly to each and every home in Komiža, via the supply line, women had the heavy duty of carrying the water to their homes. Most of the houses did not have wells or rainwater tanks so the women had to carry the water in a large metal container, so-called grotac, as much as 30 litres of water. They would place the container on their heads, which they previously protected with a cushion-like pad made from wool or old rags, to also provide support, protection and balance. They carried this heavy load all the way from the well to the house. Wells were places where women gathered and waited for their turn to fetch water, especially in the summer months when the water flow was slower and they had to wait long for their turn. This was an ideal opportunity for storytelling, and so the wells became places of women's social life, where they not only told stories about real events but also made-up, fictional stories about supernatural creatures and phenomena.

In the summer months the incoming water flow into the Dragovode Well was rather slow, and some women would come and fetch water by night because they did not need to wait in line. The path leading from Komiža to the Dragovode Well passed by the local cemetary, and only a few women were not scared of the dead. These women saved a great deal of time because they returned to their families not only with precious water but also plenty of exciting, frightning tales about encounters with the dead or other supernatural beings the previous night. Oral tradition preserved and transmitted these stories to younger generations. The water fetching era with stories wowen around the well lasted until the construction of the water supply line. The new water line extracted water from the Pizdica spring ( Small Pussy), ushering Komiža into a new age and a new world in which women were freed from the greatest burden they had been entrusted with in their households – fetching water.

9. MUSTER –A STORY ABOUT BOAT BURNING

The Church of Saint Nicholas was erected by the Benedictines who had monasteries on the islands of Svetac and Biševo. These monasteries were erected along the Benedictine Route which leads from the Gargano Peninsula via Palagruža and Komiža to the eastern Adriatic coast and the other way around. This is the route through which Christianity arrived from the Apenine Peninsula to the eastern Adriatic coast, and this church, and the former Benedictine monastery fortified for defense against the pirates, is the most important station on the Benedictine trans-Adriatic route. This church was visited by Pope Alexander III on March 10th 1177, of which there is written record on a stone plate inside the church. There is a large mid-18th century wooden altar in the sanctuary. Wooden altars in this and other churches on the island generally represent the most comprehensive period of Reneissance and Baroque wood carving in Dalmatia. In the floor of this church which eventually became a parish church and a burial ground, there are tombstones of Komiža families Vitaljić, Mardešić, Marinković and others.

On Saint Nicholas’ Day, December 6th each year, Komiža locals partake in an ancient rite practiced for hundreds of years – sacrificial boat burning. For centuries Komiža turned to the sea for its sustenance. To the fishermen of Komiža the boat is more than just a regular object used for sailing and fishing. She is a family member, a living being, born and baptized, and after closing in on her life cycle she is hauled up to the Saint Nicholas Church on the hill overlooking Komiža, and burned on a sacrificial pyre in front of the church.

The fire closes one life cycle of the boat, and brings in a new one. A new boat is born of the ashes of the burned one. The rhythm of life is determined by death and birth. Ancient knowledge in boatbuilding was taken up by new boatbuilders. The invisible thread of experience and tradition connected many generations throughout history. Today this valuable connection is terminated. Present-day falkuša boats in Komiža are the last boats “born” of this sacrificial fire.

10. DRY-STONE WALLS – A STONE “MANUSCRIPT”

There exists a wall in this world much longer than the one considered the longest in the world – a wall multiple times longer than the Chinese Wall. This wall can be found in Dalmatia. However, this wall, although spreading across an area of 60 thousand kilometers (1.5 times the length of the equator), with a sizeably larger volume than that of all Egyptian pyramids together and seven times longer than the Chinese Wall, is still not honored as a monument to human labour. This is the dry-stone wall of Dalmatian vineyards! It took almost two and a half thousand years to build this wall with hands of multiple generations of Dalmatian peasants who extracted stone for construction thus turning the rock-covered unfertile fields into fertile fruit bearing terraces, and the landscape into an elaborate and elegant stone lace.

As the wine growing island, Vis has been covered in the dry-stone wall lace ever since Antiquity. This rural architecture is the visual identity of this “amphitheatre” of Komiža Bay with its incredible forms of scattered steep slopes and hills once entirely covered by vineyards. This stone manuscript of the toiling farmers and peasants, created throughout the centuries as they struggled with the harsh karst terrain and wild bushes to create small patches of fertile field, is a story about survival.This story tells us about the centuries of heavy labour by many generations who produced wine in the direst of conditions for wine-growing, in which they succeeded in conquering the uninviting stone landscape and turning it into fertile vineyard terraces stretching all the way to the tops of hills.

Aside from the geological signs that tell us about the dynamics of Earth throughout millions of years, these signs inscribed by the human hand offer us their story about man’s millennium-long struggle for survival. Reading of the landscape also includes and interprets these fascinating anthropogenic structures and miraculous stone formations inscribed into the landscape by human hand.

11. DIAPIR – AN UNDERGROUND “MUSHROOM” MADE OF A LARGE PREHISTORIC SALT MASS

During the Late Triassic the climate was dry and warm, especially in the low latitudes, where the area of the present-day island of Vis was situated. The evaporation of water increased the concentration of dissolved salt in the sea, particularly in shallow and closed lagoons where the salt was precipitated, forming evaporate rocks: gypsum (calcium sulphate with water), anhydrite (calcium sulphate) and halite (kitchen salt - NaCl).Such conditions are still to be found at low latitudes, where the climate is dry and warm such as:the Red Sea, the Dead Sea, the Persian Gulf and elsewhere.

These rocks were deeply buried in the Earth's crust, under Cretaceous limestones, and during the last few million years they were uplifted by tectonic processes, came back to the surface in the form of a salt diapir, resembling a few kilometer tall subsurface "mushroom", formed under pressure exerted onto rocks of different density. Only gypsum outcrops occur at the surface, with anhydrite relics, because anhydrite modifies itself into the gypsum when coming into contact with water near the surface, while halite (kitchen salt) is easily dissolved in the water.

12. SELO – THE OLDEST PART OF KOMIŽA

Komiža’s neighbourhood of Selo was built further away from the port to provide greater shelter from possible pirate attacks. The houses were built mostly of breccia, crushed rock deposits bound by cohesive cement. Construction with large breccia stone rocks is a feature typical for older houses. Limestone imported from the island of Korčula is the dominant building material of houses in the port of Komiža, erected only in the 19th century when there was no more pirate danger in the Adriatic.

This part of Komiža was populated mainly by peasants – winegrowers who cultivated not only the flat fields of the spacious Komiža Bay, but also the steep slopes of the surrounding hills. This bay was known for its grape variety of bugava, native to the very island of Vis, which draws us to the conclusion that it was brought here by the Greek colonists as early as the 4th century BC. This ancient grape variety yielded exquisite white wine exported even to Franceduring the time when European vinyards were ravaged by phylloxera in the late 19th century.

Caper bushes often grow from the stone walls of houses. It appears as if they grow from the very stone, but they thrust their roots deep through the stone blocks of houses in search of soil. Their buds are conserved invinegar and consumed as a favourite side dish to salted sardines or anchovies. One such caper bush is still growing on the oldest house in Komiža, located at the beginning of the narrow Španjulovo street.

Two houses still standing at the beginning of Španjulovo street were probably builtaround the same time as the Benedictine monastery. They are both built from breccia. One of the houses has a doorstep and a lintel made of wood at least eight hundred years old. The other house features an arch-shaped lintel in a Romanesque style. They both have roofs made of stone slates. Most of the houses are deserted because their former inhabitants scattered across the world, mostly to San Pedro in California where there are twice as many Komiža descendants today than there are people in Komiža.

13. RIVA – KOMIŽA’S IDIOM

Riva is the port area. This public waterfront promenade is a typical feature of Dalmatian towns. Just like the Greek agora, riva is a place of human interaction, a space of intense communication, a place where people gather and exchange information, tell stories. It’s a place where boats come and go, fish is unloaded, deals are made, stories told, strolls taken and boats watched over when menacing weather looms from the horizon on the open sea, which Komiža faces. This is a space where a stranger will most surely come across a unique language spoken by the locals, incomprehensible and unintelligible to all outside of the community.

In 2017 Croatian Ministry of Culture included the local Vis chokavian idiomon the list of the intangible cultural goods of Croatia. According to the UNESCO Convention on the protection of intangible cultural heritage (Paris, 2003), language is the most significant part of intangible heritage because it preserves and transmits the collective memory of society. Idiom of the Vis island is today its most endangered heritage which needs to be researched and preserved for future generations. It is unique for its Slavic archaisms, as the oldest Slavic idiom on the eastern Adriatic, and it is also unique for the fact it has preserved the lexicon of the “lingua franca” idiom, used by seafarers and fishermen throughout all the Mediterranean coasts.

14. CAROB – SAINT JOHN'S BREAD

Carob (Ceratonia siliqua) is a highly valuable Biblical plant. Saint John the Baptist fed on carob tree fruit during his time in the desert. Carob was the daily bread of pyramid builders in Egypt, Mohamed’s army and the Roman legions. It sustained seafarers through their long journeys, and galley slaves chained to their rowing seats. Carob tree fruit is an ideal survival food – it lasts for a long time, does not require special storage, can be consumed directly without any preparation, and provides the human organism with everything necessary for survival.

Carob orchards with hundreds of years old trees can be found in Komiža. This is also home to a native variety of carob, the so-called thick Komiža carob, (tusti rogač) characterized by a lush and wide crown bringing forth abundant fruit with regular frequency. The fruit of this native variety is of exceptional quality, large in size, wide and fleshy. Hundreds of years of hard toil and farming knowledge applied by Komiža’s population resulted in this high quality variety, one of the best around.

In addition to the fruit, carob tree also has a highly valuable seed. Carob seeds are small, hard and possess a steady mass. The word carat is a measure for precious metals, and is derived from the Arabic word quirat, or the Greek word kerátion which designated the carob seed, once used as the first measure unit for weighing gold. It was believed that each seed weighed 0, 18 grams regardless of the shape. This was recently proved to be inaccurate since minimum variations in mass were recorded, however, back in the day this was the only reliable way to measure the weight of gold.

The place of the carob tree origin is the Persian Gulf, from which it spread towards Anatolia (Asia Minor) and the regions of Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Israel and Egypt. As early as 2000 years BC the carob tree culture was accepted by Phoenicians and spread throughout the shores of the Mediterranean. Carob tree found its way to Dalmatia via the Greek colonists who founded their city states on Dalmatian islands. In the 4th century BC Greeks from Syracuse founded the town of Issa in the Bay of St. George (present-day town of Vis) on the island of Vis. The Greeks brought grapevine and carob tree to the island. During Venetian rule the town of Komiža became the largest carob tree habitat in Dalmatia, and Venice even passed a set of laws in an attempt to stimulate the planting of new trees. One of the requirements for the marriage contract, for example, was the plantation of a certain number of new carob trees.

15. MOLO BONDA

This Komiža neighbourhood is called Molo Bonda, and is mainly populated by fishermen families. This is where the name of the street comes from – Ribarska, or the Fishermen Street. An interesting combination of various types of rock is noticeable on the facades of houses. In addition to limestone blocks, there are also breccia blocks: interesting examples of geoarchitecture. Fishermen houses on this street have in most cases three floors, but there are houses with four floors as well. The construction principle was based on building as much as possible while taking up the least amount of land surfacein order not to use up the surrounding fertile fields. The other reason was the need to keep the houses as close to the sea as possible, to enable the communication between the fishing boats and the houses. Many fishing houses by the sea had ground-level rooms used for salting and preservation of salted fish. These were so-called fishermen barracks, which were actually small family factories exporting thousands of barells of salted fish.

This street is a memory lane – on it one can find stone plates with inscribed names of the famous people of Komiža: a writer, a philosopher and a painter. Andrija Vitaljić (1652 – 1737) – priest and writer in the Baroque period in Croatian literature; he wrote in the spirit of counterreformation, with a style of Baroque flamboyance. His work represents a great contribution to the standardization of Croatian language on the Shtokavian basis. Antun Petrić (1829 – 1908) – priest and philosopher; made famous as an aesthetician with his renowned discsussion on beauty: „La Definizione del Bello“. Vinko Foretić (1888 - 1958) educated at the Art Academy in Munich, lived in Paris for a number of years where he kept company of great Parisian painters, gained attention and revered cubist; returned to Komiža in the wake of his illness, where he remained until his death, painting portraits of Komiža locals and fishing motifs.

16. PIZDICA - WATER ON THE CONTACT POINT OF DIAPIR AND CARBONATES –THE ABANDONED "BLIND" GYPSUM PIT

At the contact point of diapir, composed of impermeable volcanic rocks, and permeable carbonate rocks, in the Cove of the symbolic name Pizdica (Pussy), the first waterwell forthe water supplyline of Komiža was built in 1964.

In that very cove, there is an opening in a rock near the beach,from which a stream of potable water runs all year long, ending in the sea. This spring was restored in 2015 and still represents a significant source of potable water for Komiža and the island of Vis. In the tectonic (diapiric) contact with Cretaceous carbonate rocks we come acrosspetrified mud and gypsum. The northern part of the Pizdica Cove is made of petrified mud and volcanic ash mixture. The central part of the Cove is built up from gypsum, whereas the southern part is a large subvertical fault plane at the contact with carbonate rocks. Along this plane Triassic rocks began to rise from the depth because of salt which is of lower density than the surrounding rocks.

After WWII there were attempts at gypsum mining in the Pizdica Bay, but back then no one was aware of the fact that the rocks were structurally “like a mushroom”, and the mining attempts were brought to an end after a hard limestone rock from Cretaceous was encountered.

17. THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY MARY “THE PIRATESS”

The Renaissance church of Saint Mary “the Piratess” was built in the 16th century on the pebble beach on the northern part of Komiža Bay. Its popular nickname “Piratess” came from the legend of the pirate robbery of the church. According to this legend, the pirates robbed the church and took with them the painting of Madonna. But when they tried to set sail, their boat could not move. They attempted to start the boat in vain, however, with no success. They then decided to return the painting of Madonna, and when they did so, the boat finally moved and they sailed away. In the Baroque period, side aisles were added to the central Rennaisance nave. Its interior features Baroque altars, paintings and a wooden crucifix, as well as the the oldest preserved Dalmatian organ, constructed in 1670 by the Polish monk Stjepan Kilarević from Krakow and renovated multiple times since. The central altar is erected above a freshwater spring which flows through a canal below the church floor into a well in the courtyard. Above the altar is an octagonal crown with rustic Baroque reliefs and Biblical scenes (1705).

Both this location and the Kamenice beach as well are good examples of the geological foundation which retains fresh water. Impermeable substratum enables the freshwater spring to surface at this location, and subsequently be directed towards and collected in the well, which was for centuries a valuable source of water to the nearby families. The church courtyard was the gathering place of women who waited in line to fetch water and carry it back home in metal or wooden containers on their heads.

18. GYPSUM AND QUATERNARY BRECCIA

Breccia, the type of stone which consist of broken rocks and bound substances, is found here around the city’s Gusarica (Piratess) beach. There are two types of breccia found on this site.

The gypsum breccia, lifted up to the surface by the force of the salt diapir, contains different fragments of petrified muddy rocks and fragments of volcanic rocks from the ancient volcanic pool.These older but softer breccia rocks are breaking off in blocks by the sea (due to abrasion), andare partially covered with younger but more solid slope (talus) breccias formed during the Quaternary period.

We can recognize Quaternary breccia by its red colour. These are the youngest rocks of the Komiža Bay and the most accessible solid construction material used for construction of numerous stone houses in the area of Komiža. They were formed by the crushing of carbonate rocks along the tectonic (faulting) contacts by the protruding salt diapir. The space between the fragments of crushed rocks was filled with red soil.This material (talus/scree) has petrified,over the course of the last few hundred thousand years, into the hard rock – Quaternary breccia.